The Symbolic Phallus in Hinduism and Buddhism Is Art Is Known as

Fragment of a 4-faced linga, 900–one thousand. Central Republic of india. Sandstone. Courtesy of the Asian Art Museum, Gift of Edward Nagel, B71S10.

Fragment of a 4-faced linga, 900–one thousand. Central Republic of india. Sandstone. Courtesy of the Asian Art Museum, Gift of Edward Nagel, B71S10.

Hinduism is 1 of the globe's oldest religions. It has complex roots, and involves a vast array of practices and a host of deities. Its plethora of forms and beliefs reflects the tremendous diversity of Republic of india, where well-nigh of its one billion followers reside. Hinduism is more than than a organized religion. It is a culture, a fashion of life, and a code of behavior. This is reflected in a term Indians use to describe the Hindu organized religion: Sanatana Dharma, which means eternal faith, or the eternal mode things are (truth).

The word Hinduism derives from a Western farsi term denoting the inhabitants of the state across the Indus, a river in nowadays-twenty-four hours Islamic republic of pakistan. By the early nineteenth century the term had entered popular English usage to describe the predominant religious traditions of South Asia, and information technology is now used by Hindus themselves. Hindu behavior and practices are enormously various, varying over time and amidst individuals, communities, and regional areas.

Different Buddhism, Jainism, or Sikhism, Hinduism has no historical founder. Its authority rests instead upon a large body of sacred texts that provide Hindus with rules governing rituals, worship, pilgrimage, and daily activities, among many other things. Although the oldest of these texts may date dorsum four thousand years, the earliest surviving Hindu images and temples were created some ii thou years later.

What are the roots of Hinduism?

Hinduism developed over many centuries from a variety of sources: cultural practices, sacred texts, and philosophical movements, also every bit local popular beliefs. The combination of these factors is what accounts for the varied and diverse nature of Hindu practices and beliefs. Hinduism developed from several sources:

Prehistoric and Neolithic civilisation, which left material show including arable stone and cave paintings of bulls and cows, indicating an early involvement in the sacred nature of these animals.

The Indus Valley civilization, located in what is now Pakistan and northwestern India, which flourished betwixt approximately 2500 and 1700 B.C.E., and persisted with some regional presence as late as 800 B.C.E. The civilization reached its high point in the cities of Harrapa and Mohenjo-Daro. Although the physical remains of these large urban complexes accept not produced a peachy deal of explicit religious imagery, archaeologists take recovered some intriguing items, including an abundance of seals depicting bulls, among these a few infrequent examples illustrating figures seated in yogic positions; terracotta female figures that propose fertility; and small anthropomorphic sculptures made of stone and statuary. Material evidence found at these sites also includes prototypes of stone linga (phallic emblems of the Hindu god Shiva). Later textual sources assert that indigenous peoples of this area engaged in linga worship.

According to contempo theories, Indus Valley peoples migrated to the Gangetic region of Bharat and blended with ethnic cultures, afterwards the decline of civilization in the Indus Valley. A separate grouping of Indo-European speaking people migrated to the subcontinent from West Asia. These peoples brought with them ritual life including burn sacrifices presided over past priests, and a fix of hymns and poems collectively known as the Vedas.

The indigenous behavior of the pre-Vedic peoples of the subcontinent of India encompassed a variety of local practices based on agrarian fertility cults and local nature spirits. Vedic writings refer to the worship of images, tutelary divinities, and the phallus.

Common to virtually all Hindus are certain beliefs, including, but non express to, the following:

- a conventionalities in many gods, which may be seen as manifestations of a single unity. These deities are linked to universal and natural processes.

- a preference for one deity while not excluding or disbelieving others

- a belief in the universal constabulary of cause and effect (karma) and reincarnation

- a conventionalities in the possibility of liberation and release (moksha) by which the countless cycle of nativity, expiry, and rebirth (samsara) can be resolved

The Hindu deities Shiva and Vishnu combined equally Harihara, 600–700. Central India. Sandstone.Courtesy of the Asian Art Museum, Museum purchase, B70S1.

Hinduism is bound to the hierarchical structure of the degree organization, a categorization of members of society into defined social classes. An individual'southward position in the caste system is thought to be a reflection of accumulated merit in by lives (karma).

Observance of the dharma, or beliefs consistent with i'southward caste and status, is discussed in many early on philosophical texts. Non every religious practice can be undertaken past all members of guild. Similarly, different activities are considered appropriate for different stages of life, with study and raising families necessary for early stages, and reflection and renunciation goals of after years. A religious life demand not be spiritual to the exclusion of worldly pleasures or rewards, such as the pursuit of textile success and (legitimate) pleasure, depending on one's position in life. Hindus believe in the importance of the ascertainment of appropriate beliefs, including numerous rituals, and the ultimate goal of moksha, the release or liberation from the countless cycle of birth.

Moksha is the ultimate spiritual goal of Hinduism. How does ane pursue moksha? The goal is to reach a point where y'all detach yourself from the feelings and perceptions that tie y'all to the globe, leading to the realization of the ultimate unity of things—the soul (atman) connected with the universal (Brahman). To become to this point, one can pursue various paths: the manner of knowledge, the manner of advisable actions or works, or the way of devotion to God.

Principal Texts of Hindusim

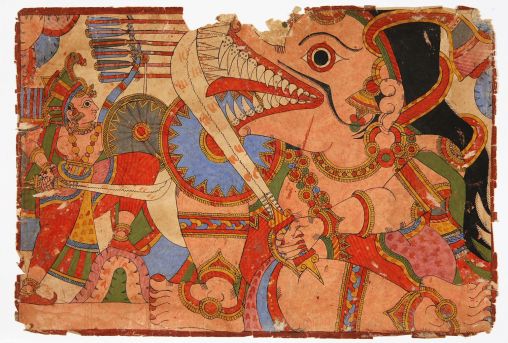

Babhruvahana fights the demon Anudhautya from a series illustrating the Mahabharata, 1830–1900. India; Maharashtra land. Opaque watercolors on paper.Courtesy of the Asian Art Museum, Gift of Walter and Nesta Spink in honor of Forrest McGill, 2010.464.

While there is no one text or creed that forms the basis of all Hindu beliefs, several texts are considered primal to all branches of Hinduism. These texts are generally divided into two principal groups: eternal, revealed texts, and those based upon what humanity has learned and written downwards. The Vedas are an example of the former, while the 2 bully epics, the Mahabharata and Ramayana, vest to the latter category. For centuries, texts were transmitted orally, and the priestly caste, or brahmins, was entrusted with memorization and preservation of sacred texts.

The Vedas

The Vedas are India's earliest surviving texts, dating from approximately 2000 to 1500 B.C.E. These texts are made up of hymns and ritual treatises that are instructional in nature, forth with other sections that are more than speculative and metaphysical. The Vedas are greatly revered by contemporary Hindus every bit forming the foundation for their deepest beliefs.

The early Vedas refer often to certain gods such as Indra, the thunder god, and Agni, who carries messages between humans and the gods through fire sacrifices. Some of these gods persist in later Hinduism, while others are macerated or transformed into other deities over time. The Vedas are considered a timeless revelation, and a source of unchanging knowledge that underlies much of nowadays-day Hindu practices.

Mahabharata and Ramayana

These ii great epics are the most widely known works in India. Every child becomes familiar with these stories from an early age. The Mahabharata is the world'southward longest poem, with approximately 100,000 verses. Information technology tells the story of the conflict betwixt the Pandava brothers and their cousins the Kauravas, a rivalry that culminates in a great battle. On the eve of the boxing, the Pandava warrior Arjuna is distressed by what will happen. The god Krishna consoles him in a famous passage known every bit the Bhagavad-Gita (meaning "the Song of the Lord"). This section of the Mahabharata has become a standard reference in addressing the duty of the individual, the importance of dharma, and humankind'south relationship to God and gild.

A second epic, the Ramayana, contains some of India'due south best-loved characters, including Rama and Sita, the ideal royal couple, and their helper, the monkey leader, Hanuman. Rama is an incarnation of the God Vishnu. The story tells of Rama and Sita's withdrawal to the forest subsequently being exiled from the kingdom of Ayodhya. Sita is abducted in the woods by Ravana, the evil male monarch of Lanka. Rama somewhen defeats Ravana, with the help of his blood brother and an army of monkeys and bears. The couple returns to Ayodhya and are crowned, and from that point the story has evolved to acquire different endings. Episodes of the Ramayana are often illustrated in Hindu art.

The Puranas

The Puranas are the primary source of stories about the Hindu deities. They were probably assembled between 300 to 1000 C.E., and their presence corresponds to the rise of Hinduism and the growing importance of certain deities. They describe the exploits of the gods every bit well as various devotional practices associated with them. Some of the Vedic gods—Indra, Agni, Surya—reappear in the Puranas, but figure less chiefly in the stories than practise Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, the various manifestations of the Goddess, and other angelic figures.

Tantras

Around the same time as the recording of the Puranas, a number of texts concerning ritual practices surrounding various deities emerge. They are collectively known every bit Tantras or Agamas, and refer to religious observances, yoga, behavior, and the proper choice and design of temple sites. Some aspects of the Tantras business the harnessing of concrete energies every bit a means to accomplish spiritual breakthrough. Tantric practices cross religious boundaries, and manifest themselves in aspects of Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism.

Hinduism and the Practice of Faith

Adult female, accompanied past bellboy, worships at outdoor linga shrine, 1800–1900. Northern India. Opaque watercolors on newspaper. Courtesy of the Asian Art Museum, Gift of Mr. Johnson S. Bogart, F2003.34.17.

Religion pervades many aspects of Hindu life, and religious observance is not limited to one location, time of 24-hour interval, or utilize of a particular text. It assumes many forms: in the home, at the temple, on a pilgrimage, through yogic practices, dance or music, at the roadside, by the river, through the ascertainment of 1's social duties and so on.

Puja

The general term used to draw Hindu worship is puja—the most common forms of worship taking place in the home at the family unit shrine and at the local temple. Practices vary depending on location, but generally speaking, the worshiper might approach the temple to give cheers, to ask for assistance, to give penance, or to contemplate the divine. Worship is tied to the individual or family grouping, rather than a service or congregational gathering. Puja occurs on a daily basis, or even several times throughout the day, likewise as at specific times and days at local temples, and with abundant festivities on the occasions of great festivals.

In the temple, the devotees are assisted by the priest, who intercedes on their behalf by performing ritual acts, and blessing offerings. Worship often begins by circumambulating the temple. Inside the temple, the priest's actions are accompanied by the ringing of bells, passing of a flame, and chanting. Traditionally, dance also formed an essential part of temple worship.

Darshan

A key concept in the worship of Hindu deities is the act of making eye contact with the deity (darshan). The activity of making direct visual contact with the god or goddess is a two-sided event; the worshiper sees the divinity, and the divinity as well sees the devotee. This ritualistic viewing occurs between devotee and God in intimate domestic spaces, every bit well as in tremendously crowded temple complexes where the individual may be part of a throng of hundreds or thousands of other worshipers. It is believed that by having darshan of the god's image, one takes the free energy that is given by the deity, and receives blessings.

This essential Hindu practise also demonstrates the profound importance of religious imagery to worship and ritual. While in about other religious traditions images are believed to represent or propose divine or holy personages, or are altogether forbidden, in Hindu practice painted and sculpted images are believed to genuinely embody the divine. Advisable ritual imbues images with authentic divine presence. Literal concrete connection in the course of visual contact is essential to religious devotion, whether on a local and ongoing ground, or in the undertaking of great pilgrimages.

Hindu temples

Click hither to view this video.

Video from the Asian Art Museum.

Sacred space and symbolic form at Lakshmana Temple, Khajuraho (India)

Sculpture of a woman removing a thorn from her foot, northwest side exterior wall, Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, Bharat, defended 954 C.Eastward.

Ideal female beauty

Await closely at the image to the left. Imagine an elegant woman walks barefoot along a path accompanied by her attendant. She steps on a thorn and turns—adeptly bending her left leg, twisting her body, and arching her back—to signal out the thorn and ask her attendant'southward assistance in removing it. As she turns the viewer sees her face up: it is round like the full moon with a slender nose, plump lips, arched eyebrows, and eyes shaped like lotus petals. While her right manus points to the thorn in her foot, her left paw raises in a gesture of reassurance.

Images of beautiful women like this one from the northwest exterior wall of the Lakshmana Temple at Khajuraho in Republic of india take captivated viewers for centuries. Depicting idealized female beauty was important for temple compages and considered cheering, even protective. Texts written for temple builders depict different "types" of women to include inside a temple'due south sculptural program, and emphasize their roles as symbols of fertility, growth, and prosperity. Additionally, images of loving couples known as mithuna (literally "the state of being a couple") appear on the Lakshmana temple as symbols of divine union and moksha, the final release from samsara (the cycle of death and rebirth).[1]

The temples at Khajuraho, including the Lakshmana temple, have become famous for these amorous images—some of which graphically depict figures engaged in sexual intercourse. These erotic images were not intended to be titillating or provocative, simply instead served ritual and symbolic part meaning to the builders, patrons, and devotees of these captivating structures.[2]

Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur Commune, Madhya Pradesh, India, defended 954 C.Eastward. (Chandella catamenia), sandstone (photo: Christopher Voitus, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Chandella dominion at Khajuraho

Location of Khajuraho, India

The Lakshmana temple was the first of several temples built by the Chandella kings in their newly-created capital of Khajuraho. Between the 10th and 13th centuries, the Chandellas patronized artists, poets, and performers, and built irrigation systems, palaces, and numerous temples out of sandstone. At one time over eighty temples existed at this site, including several Hindu temples defended to the gods Shiva, Vishnu, and Surya.[3] At that place were also temples congenital to honor the divine teachers of Jainism (an ancient Indian religion). Approximately 30 temples remain at Khajuraho today.

The original patron of the Lakshmana temple was a leader of the Chandella clan, Yashovarman, who gained control over territories in the Bundelkhand region of central India that was once part of the larger Pratihara Dynasty. Yashovarman sought to build a temple to legitimize his dominion over these territories, though he died before it was finished. His son Dhanga completed the piece of work and dedicated the temple in 954 C.E.

Nagara style architecture

Vaikuntha Vishnu, womb chamber (garba griha), Lakshmana temple. 1076-1099 C.East., sandstone (photo: Christine Chauvin, CC Past-NC-ND 2.0)

The cardinal deity at the Lakshmana temple is an prototype of Vishnu in his three-headed form known as Vaikuntha[four] who sits inside the temple'southward inner womb chamber as well known every bit garba griha (above)—an architectural feature at the center of all Hindu temples regardless of size or location. The womb chamber is the symbolic and concrete cadre of the temple's shrine. It is dark, windowless, and designed for intimate, individualized worship of the divine—quite different from large congregational worshipping spaces that characterize many Christian churches and Muslim mosques.

The Lakshmana Temple is an excellent example of Nagara style Hindu temple architecture.[five] In its most basic form, a Nagara temple consists of a shrine known as vimana (essentially the shell of the womb chamber) and a flat-roofed entry porch known as mandapa. The shrine of Nagara temples include a base platform and a large superstructure known as sikhara (meaning mount height), which viewers tin can run into from a distance.[6] The Lakshmana temple'due south superstructure appear like the many ascent peaks of a mountain range.

Plan of Lakshmana temple

Approaching the divine

Devotees approach the Lakshamana temple from the eastward and walk around its entirety—an activity known equally circumambulation. They begin walking along the big plinth of the temple'due south base, moving in a clockwise direction starting from the left of the stairs. Sculpted friezes along the plinth depict images of daily life, dear, and war and many retrieve historical events of the Chandella period (meet paradigm below and Google Street View).

Section of a narrative frieze encircling the temple at the level of the plinth, Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur Commune, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 (photograph: Sheep"R"United states of america, CC By-NC-ND ii.0)

Ganesha in niche, exterior mandapa wall, south side, Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 (photo: Manuel Menal, CC By-SA 2.0)

Devotees and then climb the stairs of the plinth, and encounter another set up of images, including deities sculpted within niches on the outside wall of the temple (view in Google Street View).

In i niche (left) the elephant-headed Ganesha appears. His presence suggests that devotees are moving in the correct direction for circumambulation, as Ganesha is a god typically worshipped at the beginning of things.

Other sculpted forms appear nearby in lively, active postures: swaying hips, bent arms, and tilted heads which create a dramatic "triple-bend" contrapposto pose, all carved in deep relief emphasizing their 3-dimensionality. It is here —specifically on the outside juncture wall between the vimana and the mandapa (encounter diagram above)—where devotees encounter erotic images of couples embraced in sexual marriage (see prototype beneath and here on Google Street View). This identify of architectural juncture serves a symbolic office as the joining of the vimana and mandapa, accentuated past the depiction of "joined" couples.

Four smaller, subsidiary shrines sit at each corner of the plinth. These shrines appear similar miniature temples with their own vimanas,sikharas, mandapas, and womb chambers with images of deities, originally other forms or avatars of Vishnu.

Following circumambulation of the exterior of the temple, devotees see 3 mandapas, which prepare them for entering the vimana. Each mandapa has a pyramidal-shaped roof that increases in size as devotees movement from east to due west.

Figural groupings on the temple exterior including Shiva, Mithuna, and erotic couples, Lakshmana temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 (photo: Antoine Taveneaux, CC By-SA 3.0). View this on Goole Street View.

Once devotees pass through the tertiary and final mandapa they discover an enclosed passage along the wall of the shrine, allowing them to circumambulate this sacred structure in a clockwise direction. The deed of circumambulation, of moving effectually the various components of the temple, allow devotees to physically experience this sacred space and with it the torso of the divine.

Archway to the Mandapa, Lakshmana Temple, Khajuraho, Chhatarpur District, Madhya Pradesh, India, dedicated 954 (photograph: Antoine Taveneaux, CC BY-SA iii.0)

Notes:

[1] Mithuna figures appear on numerous Hindu temples and Buddhist monastic sites throughout South asia from as early equally the 1st century C.East.[2] Some scholars suggest that these erotic images may be connected to Kapalika tantric practices prevalent at Khajuraho during Chandella dominion. These practices included drinking wine, eating flesh, man sacrifice, using human skulls as drinking vessels, and sexual union, particularly with females who were given key importance (as the seat of the divine). The idea was that past indulging in the bodily and material world, a practitioner was able to overcome the temptations of the senses. However, these esoteric practices were generally looked downward upon past others in South Asian society and accordingly very often were washed in secrecy, which raises questions almost the logic of including Kapalika-related images on the exterior of a temple for all to see.[3] In that location is too at least one temple at Khajuraho, the Chausath Yogini Temple, dedicated to the Hindu Goddess Durga and 64 ("chausath") of her female attendants known every bit yoginis. It was built by a previous dynasty who ruled in the expanse before the Chandella kings rose to power.[4] The original Vaikuntha at Lakshmana temple was itself politically pregnant: Yashovarman took it from the Pratihara overlord of the region. Susan Huntington indicates that the stone image currently on view at Lakshmana temple, while indeed a form of Vaikuntha, is not in fact the original (metallic) image which Yashovarman appropriated from the Pratihara ruler. Appropriating some other ruler'south family deity as a political maneuver was a widespread practice throughout South asia. For more than on this practice, see the piece of work of Finbarr B. Overflowing, Objects of Translation: Fabric Culture and Medieval 'Hindu-Muslim' Come across (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), particularly Chapter iv. A similar Vaikuntha paradigm now appears in the primal shrine of the Lakshmana temple and is notable for its depiction of the deity's iii heads with a man face at the front (east), a lion's confront on the left (south), and a boar's face up on the correct (north)—the latter two of which are at present desperately damaged. An implied, though non visible 4th confront is that of a demon's caput at the rear of the image (west-facing) which has led some scholars to identify this class as Chaturmurti or four-faced.[5] In general, there are ii main styles of Hindu temple architecture: the Nagara mode, which dominates temples from the northern regions of India, and the Dravida style, which appears more frequently in the South.[6] The base platform is sometimes known every bit pitha, significant "seat." A flattened bulb-shaped topper known as amalaka appears at the top of the superstructure or sikhara. The amalaka is named later on the local amla fruit and is symbolic of abundance and growth.

Varanasi: sacred city

Click here to view this video.

Video from the Asian Art Museum

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sac-asianarthistory/chapter/hinduism/

0 Response to "The Symbolic Phallus in Hinduism and Buddhism Is Art Is Known as"

Post a Comment